For decades, scientists have debated whether nonhuman animals experience joy, or “positive affect,” as they call it in scientific circles. While we assume our pets and other creatures feel happiness, proving it has been elusive. Now, a global team of researchers is embarking on an ambitious project: developing a “joy-o-meter” – a set of measurable metrics to quantify happiness in animals.

The Historical Hurdles

The study of animal emotions has been historically sidelined by scientific methodology. Early 20th-century behaviorism, exemplified by Pavlov’s conditioned dogs and Skinner’s lever-pressing rats, focused exclusively on objectively measurable actions, effectively dismissing subjective experiences like feelings as unscientific.

While negative emotions – fear, pain, suffering – were studied extensively (driven by the need to relieve them in humans and animals), positive affect remained taboo. This reluctance stemmed from a fear of anthropomorphism – attributing human qualities to nonhuman entities.

However, pioneers like neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp challenged this bias, demonstrating that rats emit laughter-like sounds when tickled, a finding initially met with skepticism.

The New Push for Positive Affect

Today, researchers recognize that studying joy isn’t just about understanding animal welfare; it could unlock insights into happiness itself. The current effort, funded by the Templeton World Charity Foundation, aims to create universal metrics applicable to diverse species.

The challenges are significant. Measuring happiness isn’t as straightforward as identifying fear responses. Researchers must first define joy – an intense, brief positive emotion triggered by an event – and then identify reliable indicators.

Key Experiments: Apes, Parrots, and Dolphins

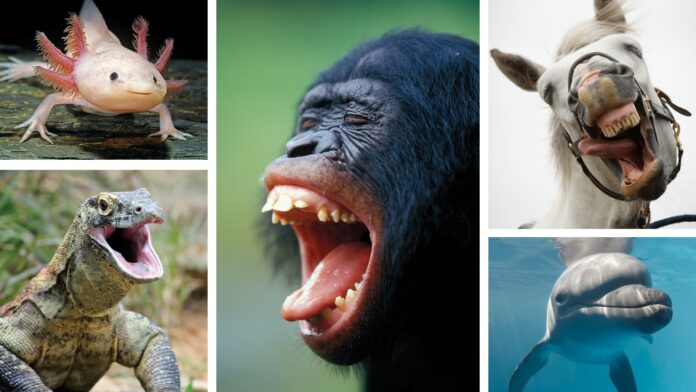

The team is conducting experiments across several species, starting with great apes due to their genetic proximity to humans. Studies at the Fongoli Savanna Chimpanzee Project in Senegal and zoos in Belgium, Iowa, and Florida are analyzing behaviors like playful interactions, grooming, and vocalizations for signs of joy.

Researchers are triggering “joyful moments” through novel stimuli. Bonobos at the Ape Initiative in Des Moines responded positively to recordings of baby bonobo laughter, showing increased curiosity toward gray boxes (potentially signaling optimism). Windfall experiments, like surprise treats or reunions with keepers, are also being used to observe reactions.

Meanwhile, studies on kea parrots in New Zealand face an unexpected hurdle: captive-bred birds had never heard warble calls (their natural “giggle fits”) and reacted with distress, highlighting the complexity of triggering joy in a controlled environment. Researchers are now experimenting with food windfalls, like offering peanut butter after a series of less-desired carrots.

Dolphin studies, led by Heidi Lyn at the University of South Alabama, are also underway, aiming to identify similar emotional cues in aquatic mammals.

The Long-Term Implications

This research isn’t just about satisfying scientific curiosity. A reliable “joy-o-meter” could revolutionize animal welfare in captivity, allowing for better enrichment and reducing suffering. More fundamentally, it might shed light on the biological basis of happiness across species, potentially offering clues to human well-being.

As biopsychologist Gordon Burghardt points out, “What is it that makes a good life? Those are the topics that are most worthwhile for us.” The quest to measure joy in animals may ultimately help us understand joy itself.