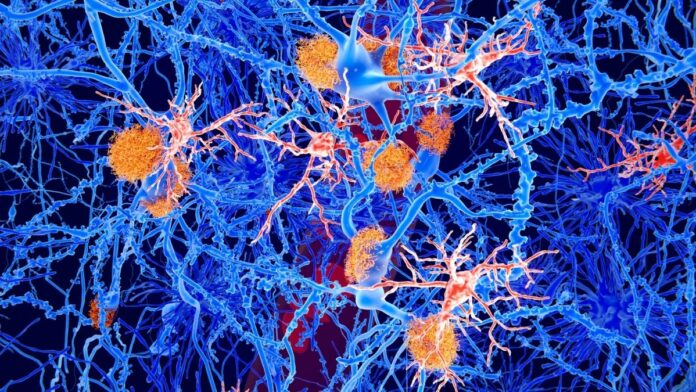

Scientists have discovered a potential new approach to treating Alzheimer’s disease by using specially engineered ‘young’ immune cells. According to a study conducted on mice, these lab-manufactured immune cells were able to reverse some of the cognitive decline and brain damage associated with the disease.

The aging immune system

The immune cells in question are called mononuclear phagocytes. In younger organisms, these cells efficiently clean up cellular waste throughout the body. However, as we age, these “immune-cell cleaners” become less effective, clearing away less debris and triggering more inflammation.

This decline in immune function contributes significantly to age-related diseases, including Alzheimer’s. Chronic inflammation and abnormal protein accumulation are key features of both aging and neurodegenerative conditions.

Engineering young immune cells

Researchers at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in the United States reprogrammed human stem cells to create young versions of these protective immune cells. These induced pluripotent stem cells were transformed into functional mononuclear phagocytes that could potentially counteract the effects of aging.

“This approach uses young immune cells that we can manufacture in the lab,” explained Dr. Clive Svendsen, a biomedical scientist involved in the study. “We found that these engineered cells have beneficial effects in aging mice and in models of Alzheimer’s disease.”

Measurable improvements

The experimental treatment yielded several notable benefits. Mice that received the young immune cells performed better on memory tests compared to control groups. Additionally, these animals showed healthier brain cells called microglia, which are crucial for maintaining brain health.

Interestingly, the researchers observed an increase in mossy cells – specialized brain cells that support memory function in the hippocampus region. These cells, like their immune counterparts, are vulnerable to age-related decline and Alzheimer’s disease.

“We didn’t see the typical decline in mossy cells in the treated mice,” noted lead researcher Dr. Alexandra Moser. “This likely contributed to some of the memory improvements we observed.”

How the treatment works

The engineered immune cells appear to secrete beneficial substances that travel through the body and reach the brain. Rather than directly repairing brain damage, these “young” cells seem to work by improving overall immune function and reducing inflammation.

“Our findings suggest that the cells release anti-aging proteins or extracellular vesicles that communicate with other cells,” explained Dr. Moser. “These factors likely create a healthier environment for brain cells to function.”

Next steps

While these results are promising, important limitations must be acknowledged. The study was conducted on mice, and the effects observed may not translate directly to humans. Additionally, the research primarily focused on aging mice rather than mice with induced Alzheimer’s disease.

“These findings show that short-term treatment improved cognition and brain health,” said Dr. Jeffrey Golden, a neuropathologist who reviewed the study. “However, much more research is needed before we can consider this approach for human patients.”

Despite these caveats, the potential implications are significant. This novel approach could offer advantages over existing treatments like blood plasma transfusions or bone marrow transplants, particularly if the cells can eventually be derived from a patient’s own tissues