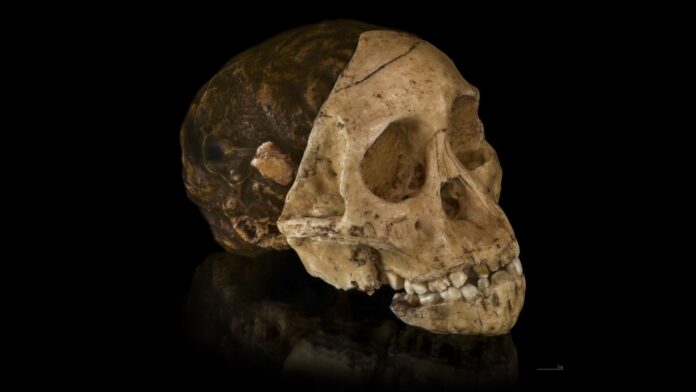

In late 1924, a fossil skull unearthed in South Africa dramatically reshaped our understanding of human evolution. This discovery, now known as the “Taung Child,” provided the first concrete evidence that Africa was the birthplace of humanity —a pivotal confirmation of Charles Darwin’s theories. The story behind its finding, however, is less about a meticulous excavation and more about serendipity and academic ambition.

The Accidental Discovery

The skull wasn’t found by the scientist credited with its analysis, Raymond Dart, but by a student named Josephine Salmons. Local quarry workers at Buxton Limeworks in Taung had already blasted the skull from the rock. It was brought to the attention of the company and then passed to Salmons, who recognized its significance and brought it to Dart’s class.

Dart, eager for further discoveries, enlisted a geologist colleague, Robert Young, to liaise with the quarryman, Mr. de Bruyn. De Bruyn eventually identified a brain cast embedded in rock and handed it directly to Dart. Notably, Dart later embellished the story in his memoir, claiming he had unearthed the skull himself from delivered crates—a detail that never happened.

The Moment of Recognition

Dart’s account describes an immediate realization of the fossil’s importance. “As soon as I removed the lid… a thrill of excitement shot through me,” he wrote. The skull, though diminutive, clearly represented a creature neither fully ape nor fully human. On December 23rd, he was able to view the skull’s face.

Within weeks, he published his findings in Nature in February 1925, naming the species Australopithecus africanus, or “The Man-Ape of South Africa.” This was the first near-complete fossil skull of an ancient hominin ever found, and it propelled Dart to scientific fame.

The Taung Child’s Legacy

The fossil was estimated to be around 2.58 million years old. The skull’s dimensions indicated a child roughly six years old, though later research suggests an age of three or four at the time of death. Researchers now believe it was a female.

For nearly half a century, A. africanus was considered our direct ancestor. However, the discovery of “Lucy” (Australopithecus afarensis ) in Ethiopia in 1974—dated to 3.2 million years ago—eventually dethroned the Taung Child as our closest known common ancestor.

The Taung Child’s discovery remains a landmark moment in paleoanthropology. Though its position in the human family tree has been refined, it was the first definitive proof that human origins lie in Africa, a claim that continues to drive research today.